- Home

- Barry Reckord

For the Reckord

For the Reckord Read online

FOR THE RECKORD

FOR THE RECKORD

A COLLECTION OF THREE PLAYS BY BARRY RECKORD

Edited by Yvonne Brewster

With contributions from Diana Athill, Pam Brighton, Mervyn Morris and Don Warrington

OBERON BOOKS

LONDON

This collection first published in 2010 by Oberon Books Ltd

Electronic edition published in 2012

Oberon Books Ltd 521

Caledonian Road, London N7 9RH

Tel: 020 7607 3637 / Fax: 020 7607 3629

e-mail: [email protected]

www.oberonbooks.com

Flesh to a Tiger copyright © 1958 Barry Reckord

Skyvers first published by Penguin in 1966 in New English Dramatists Volume

9. Copyright © 1966 Barry Reckord

White Witch copyright © 1985 Barry Reckord

Individual contributions copyright © the contributors 2010

Barry Reckord is hereby identified as author of these plays in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The author has asserted his moral rights.

All rights whatsoever in this play are strictly reserved and application for performance etc. should be made before commencement of rehearsal to Margaret Reckord Bernal; [email protected]. No performance may be given unless a licence has been obtained, and no alterations may be made in the title or the text of the play without the author’s prior written consent.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or binding or by any means (print, electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

PB ISBN: 978-1-84943-053-1

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84943-704-2

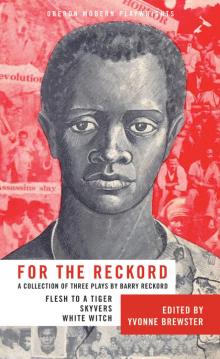

Cover design by James Illman.

Cover image: Poster by Colin Garland for the Jamaica National Theatre Trust 1972 production of In the Beautiful Caribbean by Barry Reckord. Courtesy of Lloyd Reckord.

Printed, bound and converted in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd., Croydon, CR0 4YY.

Visit www.oberonbooks.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you’re always first to hear about our new releases.

Dedicated to Lloyd Reckord

Contents

PROLOGUE

Diana Athill

INTRODUCTION

Yvonne Brewster

FLESH TO A TIGER

SKYVERS: AN APPRECIATION

Pam Brighton

SKYVERS

Introduction to WHITE WITCH

Mervyn Morris

WHITE WITCH

EPILOGUE

Don Warrington

List of works

Notes on Contributors

Acknowledgements

Prologue

In 1960, when I first met Barry Reckord, his second play, You in Your Small Corner, was about to open at London’s Royal Court Theatre. It seems, alas, that no copy of that play survives. Being about a young Jamaican’s first year in England, it was closer to his personal experience than anything else he wrote, and its run at the Court was impressive. Later it was produced again at London’s Arts Theatre, but with less success owing to a bad piece of miscasting. To my mind it was the most strikingly witty of his plays.

That is the lovely quality of his writing: not the kind of wit that produces smart word-play, but wittiness in the way things are observed. Barry was never a joke-maker, but he was always acutely aware of what was absurd or comic about life, which gave his dialogue a lot of sparkle. In the same way, the elegance of his style was the kind which results in precision, rather than in a prose which is decorative or ‘poetic’ (something which he hated). He used to say that if you could take a word out of a sentence and substitute another one without changing the sentence’s meaning, then both those words were redundant – an observation to which my own writing owes much. And this liveliness and grace of style was united with great sensitivity to moral issues, as is so powerfully demonstrated in what I think was the most admired of his plays, Skyvers.

It was a piece of dreadful bad luck that turned the tide of his rising reputation. White Witch, a marvellous play, was taken up by a producer who had enjoyed one big success in London with a play which transferred to Broadway; and Broadway was where she decided that Witch should open, so off Barry went to New York and glory. A director had already been picked, a cast chosen – and no sooner had they met for the first read-through than it became apparent that the producer’s other play was a disastrous flop. So disastrous was it that the poor woman’s career as a producer ended then and there. And Barry came home.

After that set-back, bravely though he endured it, it seemed to me that Barry’s passion for ideas for their own sake began to eclipse his interest in the making of plays – and a play which exists primarily for the propagation of an idea, as his increasingly did, leaves producers cold. Gradually, therefore, the play-going public lost sight of him. But the long diminuendo with which his writing career ended most certainly ought not to annul the fact that Barry Reckord wrote four outstanding plays, and the present fact that this book brings three of them back into circulation should give great pleasure to everyone interested in serious theatre.

Diana Athill

Introduction

Why a collection of early plays from Barry Reckord? His place in the history of black playwriting in the United Kingdom goes almost unrecognised. This is unfortunate. Reckord was among the first modern Caribbean playwrights to have work produced in England, in a period when black writing was being ‘discovered’ there. In fact a claim might even be made that he was the first of this small band to enter the scene, if one takes into account a small fringe production of his first play Della, or Adella under which title it was staged by his brother Lloyd in London in 1954.

It was at the Royal Court Theatre in Sloane Square where the majority of Caribbean playwrights of the 1950s and 1960s found a home. In 1956 Trinidadian Errol John won The Observer playwriting prize with his first play Moon on a Rainbow Shawl which was produced there, in 1957. This was followed in 1958 by Reckord’s Flesh to a Tiger, directed by Tony Richardson and designed by Loudon Sainthill. In 1960 You in Your Small Corner, written while Reckord was still a student at Cambridge, was produced by the Royal Court, directed by John Bird and produced by Michael Codron, transferring to the Arts Theatre in London’s West End. It was subsequently adapted for Television by Reckord, and was aired by Granada TV on the 5th June 1962. In 1963 his third and best known play Skyvers was presented, once again at the Court, directed by Anne Jellicoe. These successes in the 1960s were followed in the 1970s by a stage production of a new play A Liberated Woman1, Pam Brighton’s updated 1971 revival of Skyvers which transferred from the Court to the Roundhouse, and a major BBC TV production of In The Beautiful Caribbean2 adapted for television by Reckord, directed by Phillip Saville, leading to another BBC Television commission Club Havana, produced by Peter Ansorge and aired in 1975.

No scripts of Reckord’s impressive body of work are readily available. They should be. My initial thought was to pull together four of the early plays. You in Your Small Corner would have been one of those but no copy has been found. The search for the texts has been challenging. Many incomplete manuscripts exist. Complete scripts were harder to come across. Finding the prompt copy of Flesh to a Tiger in the archives of t

he Royal Court held at the Victoria and Albert Museum was a eureka moment. It turned out Diana Athill had a copy of the original version of Skyvers, and Munair Zacca, having been persuaded to hunt in his attic of play-scripts, found The White Witch of Rose Hall in which he played Palmer in 1978 in Jamaica. However, during the final edit of this book Errol Lloyd unearthed a later (White Witch 1985) edition which had been worked on by Reckord and it is this version which is used.

Reckord’s influence should be put in perspective: his achievements in England as a Jamaican abroad in the 1950s and 1960s laid a solid foundation for later emerging Caribbean playwrights such as Trinidadian Mustafa Matura, Guyanese Michael Abbensetts and Jamaican Alfred Fagon in the 1970s, all of whom appreciated how well Reckord’s work had paved their way forward.

Barry Reckord described by Edward Baugh3 as... ‘an ebullient, iconoclastic prophet, willing to be reckless in his craft in order to deliver some urgent, unequivocal social message, dictated by his muse of common sense and reason...’ was, in his own words, ‘... interested in sex and politics...and then in sexual politics which I didn’t associate with gender. I was continually talking in my plays about sex. I agree that they were thesis driven so that when...a man walked out saying, “Me come ya fi laugh, me nuh come yah fi think,” I loved that. I should’ve put that over my desk... My other theme was against power politics and power (sex). I usually saw them as the same syndrome... Most sex is conquest, and politics is conquest...’4

In 2006 Michael Billington in his review5 of the Royal Court 50th anniversary reading of the play wrote, ‘Other dramatists such as Nigel Williams in Class Enemy went on to explore the failure of the system to cope with those at the bottom of the heap. But Reckord got there first and while it is tempting to say times have changed, new figures show that up to 16million adults today have the reading and writing skills of primary schoolchildren... a piece that proves the best drama offers vital social evidence.’

So, we have three Reckord plays each written in a different decade (1950s, 1960s, 1970s) with a preface from Diana Athill, his long time friend, an introduction to Skyvers by Pam Brighton whom Barry says ‘owns’ the play by virtue of her understanding and long association with it, a detailed examination of White Witch by Mervyn Morris, and an appreciation of the writer as friend and mentor by the actor Don Warrington. For the Reckord, is hopefully, something which the growing number of new playwrights, especially but not exclusively black, will afford themselves an opportunity of reading and learning from Reckord’s work or simply enjoying the sophistication and insight of his delivery, characterisation, politics and plot.

Finally, a brief introduction to Flesh to a Tiger... It should be understood that in the Fifties and Sixties the English Stage Company operating under the artistic leadership of George Devine at the Royal Court Theatre in Sloane Square, London was in reality the only place where new playwrights had the opportunity of having their work seriously considered, given dramaturgical advice and for the lucky few their work produced. There was no National Theatre, no Hampstead, no Soho, no Tricycle, no Talawa to approach. It was the theatre of young John Osborne whose third play Look Back in Anger (1956) which ‘wiped the smugness off the frivolous face of English theatre,’6 and is credited with changing the face of modern British theatre. Thus for Jamaican Barry Reckord to have had no fewer than five of his plays, not counting in some cases second productions produced there in the face of very fierce competition from the cream of British writers such as Edward Bond, Peter Gill, John Osborne, Christopher Hampton, Anne Jellicoe and Arnold Wesker, was and remains an achievement worthy of note.

As a solitary Jamaican drama student at Rose Bruford College in 1958 vivid memories over fifty years float back to me of seeing Flesh to a Tiger at the Royal Court: travelling up to London to Sloane Square to see a Jamaican play was something which I had not had the opportunity of doing in London before. I had seen Moon on a Rainbow Shawl the previous year: that was by Trinidadian Errol John. The thought of so many Caribbean people (the performing company was over 20 strong) on a London stage was profound, but actually hearing the once familiar drums, cadences and accents of my people, seeing and feeling the power of their body language, was an altogether empowering experience. The play’s message for me lingers still. Bad medicine is bad medicine, be it black or white...

First presented under the title of Della in 1953 at Kingston’s Ward Theatre it was thought to be melodramatic by some: Cynthia Wilmot (a Canadian writer and filmmaker): ‘When it was good it was very, very good and when it was bad it was awful.’ Its name was changed to Adella for the small fringe production in London in 1954, but the 1958 title for the Royal Court production Flesh to a Tiger stuck.

I have found few people who actually saw Flesh to a Tiger in London. One such was veteran Jamaican theatre historian the late Wycliffe Bennett who happened to be in the United Kingdom at that time who recalled, ‘seeing an out of town pre-premier performance in Brighton, Sussex in 1958: I remember Cleo Laine being very dynamic in this most thought producing ground breaking play’.

The cast list read like a who’s who in Black British theatre with Cleo Laine in the leading role, Nadia Cattouse, Lloyd Reckord and others. Della is an intelligent woman living in Trench Town, one of the most dis-advantaged areas of downtown Kingston. We find her estranged from the powerful local preacher cum ‘natural doctor’ Aaron who is mortally wounded by her defection from his church and bed...

‘I order this whole yard to shake her with silence...’

She has two children, teenaged Joshie and ailing infant Tata who is being treated by a white doctor in open defiance of Aaron’s threats to kill the infant by obeah (voodoo, black magic), his stock in trade...

‘Preacher has a thin skin and a vengeful heart,’

is how he describes himself. Reckord’s play follows Della as she is buffeted by the community’s ingrained prejudice against the doctor and all he stands for, the pragmatic common sense of Joshie who sees right through the manipulative ways of the preacher and the fearful fickleness of his followers, urging his mother Della to forsake this backward approach and embrace the science which the doctor offers, and the middle class morality of the doctor who is willing to have sex with her ‘...black skin graces your beauty like a fetish glove’, but not kiss her. Della is one of Reckord’s most challenging parts for women. She is rarely off the stage; the emotional development of the play is dependent on her choices of action. After expelling her thoughts of succumbing to the patronising support of the doctor, she attempts to become a rallying point for the disenfranchised men and women of the area. Ultimately her hopes of leading them from the darkness of convenient if uncomfortable belief, into the light of modernity stand but a tiny chance of success thus leaving her with little option but the melodramatic.

‘God’s mercy fell like the bright morning over the darkness of my life...’

The play’s detailed melodically written examination of the hold which religion maintains over a population which has yet to seize true emancipation from the gravity of colonisation, created tension in the auditorium and some occasional, encouraging responses from the audience who wanted her to make the right choices in her dilemma and urged her to do so:

‘I hate the White Wolf (the name given the doctor by the community), feel abomination for Shepherd. Between them, must be a way’.

‘Keep strong Della you will find a way’ one urged silently, these sentiments occasionally escaping the lips, much to the annoyance of the British audience which usually prefers silent theatrical communion, echoed in the theatre.

The power of religion is an active, if at times cynical, player in the lives of many Jamaican people and has found its way into its literature, for example Alfred Fagon in 11 Josephine House, and Perry Henzel7 in The Harder They Come, who have also glanced enquiringly at the power of the men of God over their female preferably young nubile parishioners. But Barry Reckord, once again, was first.

Yvonne Brewster

1 Presented by the Royal Court in 1971 and at La Mama in New York in March of that year.

2 First produced by The Jamaica National Theatre Trust in 1972 as a play for the stage directed by Lloyd Reckord.

3 Jamaican academic and man of letters.

4 The Sunday Gleaner, August 10 2003 section E6, Michael Reckord.

5 The Guardian, 25 February 2006.

6 John Lahr, New York Times Book Review.

7 Director and co-author of The Harder They Come, filmed in Jamaica in 1970.

FLESH TO A TIGER

Flesh to a Tiger was first Performed at the Ward Theatre Kingston, Jamaica under the title of Della, directed by Lloyd Reckord in 1953; the UK in 1954 in a fringe production under the title Adella; and then at the Royal Court in 1958 under the title Flesh to a Tiger with the following cast directed by Tony Richardson and designed by Loudon Sainthill:

Cast

JOSHIE, Tamba Allan

LAL, Pearl Prescod

DELLA, Cleo Laine

SHEPHERD AARON, James Clarke

THE DOCTOR, Edgar Wreford

VIE, Dorothy Blondel-Francis

GEORGE, Lloyd Reckord

PAPA G, Edmundo Otero

RUDDY, Johnny Sekka

GLORIA, Nadia Cattouse

GRANNY, Connie Smith

DRUMMERS, George Johnson, Illario Pedro, Emmanuel Myers

MEMBERS OF THE BALM YARD, Ena Babb, Maureen Seale, Lloyd Innis, Vernon Trott, Berril Briggs, Keefe West, Francisca Francis

CHILDREN, Ansel Bernard, Barbara Bernard, Auguste Curtis

Characters

JOSHIE

LAL

DELLA

SHEPHERD AARON

VIE

GEORGE

PAPA G

RUDDY

GLORIA

GRANNY

DRUMMERS

For the Reckord

For the Reckord