- Home

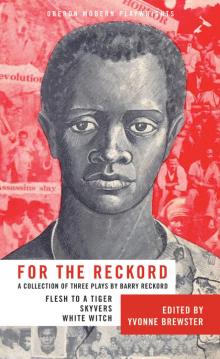

- Barry Reckord

For the Reckord Page 6

For the Reckord Read online

Page 6

Skyvers: an appreciation

When I first came across Skyvers in 1970, it struck me as a powerful, relevant and hugely articulate work. I knew it had already been produced at the Royal Court some eight years before but I was running the Young People’s Scheme there at that time and they agreed to a second production.

The gap, cultural, social and economic between the working class, or do we now call them the underclass, and the middle/upper class is a chasm. It is the running sore through our society and it amazes me how little it is written about. Skyvers was one of the first plays I ever read that really laid it out. In 1971 when I directed it, it was painfully astute; in 2007, when it was revived for a reading as part of the 50th anniversary season at The Royal Court, it remained painfully astute and relevant.

How had Barry, a Jamaican teacher, in a London comprehensive, described so accurately the alienation and rage of south London boys? The entrapment of both boys and girls bounded by sex, violence and either dull dead-end jobs or crime was described so perfectly by Barry. He had come to England, had gone to Cambridge but was black, radical and incapable of compromise. He had a ringside at what social alienation meant.

The class differences at work in most schools is particularly intense in secondary modern schools. The expectations are virtually nil, the teachers soon worn down. But the social differences have to be preserved, the rituals of middle class life: good behaviour, obedience, politeness, have got to be preserved. Only the young, still idealistic supply teacher, is prepared to not to waste time imposing rules of behaviour in the hope of discovering some positives in his class of apparent hoodlums.

Cragge, the hero of the piece, (superbly played by Michael Kitchen), is football mad, he has a notion of becoming a professional player or writing about it for the school paper. He struggles not to get dragged down by the nihilism of his peers. But ultimately fails.

John Lennon’s best song Working Class Hero has the lines, ‘they hate you if you’re clever, they despise the fool.’ Skyvers explores this contradiction that paralyses loads of working class kids. If you’re clever at school, then you’re going over to their side, you’re adopting their standards and their world. No one wants to be seen to be doing that, so you have to excel in strictly working class ways: fighting, sexual aggrandisement, crime, if you’re a boy. Sexual allure and power, if you’re a girl. It’s exactly this hopeless contradiction that Barry writes so well about, all the kids in Skyvers are being destroyed by it.

Skyvers was produced in Sloane Square in 1971, hardly the appropriate habitat for it. I was reminded of its in-appropriateness in 2007, when on the first morning of rehearsal for the revived reading, I paused at the window of a furnishing store and looked at a garden bench for sale at £600.

Back in 1971 we had to bus in kids from the same background as the kids in Skyvers and they loved it. When it transferred to the huge space in The Roundhouse the excitement among the young audience was palpable as the kids in the play crashed their desks around. Skyvers asked them the right questions: what was being done to them and what were they doing to themselves. Skyvers was a hit. It didn’t go into the West End or make any money but it was seen by the right audiences.

I think of all those 1960s, 1970s writers Barry was one of the very best. He wrote cogently and imaginatively about the world we lived in. Why is he not more rated and more successful? Well he didn’t play any of the games, he is intelligent and his plays demanded change. Whether you were black or white didn’t matter... didn’t matter if you were poor, alienated. If your life had never had a chance to begin then the world had to change so you could be part of it. And British theatre has never really been interested in change, in genuine equality: Barry is and that’s why British theatre has found it so hard to give him his place.

Pam Brighton

Skyvers was first performed on the 23rd July 1963 at the Royal Court Theatre, London, directed by Ann Jellicoe with the following cast:

CRAGGE, David Hemmings (Michael Kitchen)

BROOK, Phillip Martin (Joe Blatchley)

COLMAN, Nicholas Edmett (Mike Gredy)

ADAMS, John Hall (Billy Hamon)

JORDAN, Lance Kaufman (Jonathan Bagnor)

FREEMAN, Bernard Kay (William Hoyland)

WEBSTER, John Woodnutt (Len Tentan)

HEADMASTER, Dallas Caval (Len Tentan)

HELEN, Chloe Ashcroft (Cheryl Hall)

SYLVIA, Annette Robertson (Pam Scotcher)

The names in brackets are for the 1971 production at the Royal Court Theatre directed by Pam Brighton.

Editor’s note: Skyvers appears to have has been updated in every production it has received. The version selected is from the first performance as the essence of the play is cogent enough for it to stand as originally written.

Characters

CRAGGE

BROOK

COLMAN

ADAMS

JORDAN

Fifteen-year-old boys in a school

FREEMAN

WEBSTER

HEADMASTER

Masters

HELEN

SYLVIA

Fifteen-year-old girls

Preface

Although I have avoided any artificially heightened language and kept within the range of cockney idiom, the language in this play is clearly invented. Schoolboys, on the whole don’t talk in the way I make them talk. Usually their talk is less interesting. But if the play sounds real it is because I’ve got down what these boys do in fact think and feel, although often they are too inarticulate to say it. This, to me, is the imaginative process – the whole business of writing.

People emerge whole only when you capture convincingly their thoughts and feelings. When I hear their actual speech, it often seems too trivial to be in any way important. But this is obviously only its surface. It is the writer’s imagination that takes us beneath it, and by showing the whole person makes him invaluable.

This is a very different thing from documentary or naturalism, which I would define as the capturing of surface reality. Writers always want to get away from the surface. They want to reflect the underbelly of feeling, and in the attempt always have to face the crucial question of speech. They all have to heighten speech, but how? Do they heighten in within the common idiom, or do they go outside it, use phrases that people would never say, artificially heighten? This is in one form or another the underlying debate in recent drama. What is heightened speech? It is an old question, but absolutely crucial. For me, heightened speech is ordinary speech which is at the same time perceptive – the kind of thing one could put quite naturally into the mouth of some old cockney Lear: ‘I’ll do things… What, I don’t know… I’ll be a terror’. The best word for this is realism, and realism should never be confused with naturalism. The distinction is useful. Naturalistic speech is ordinary which is commonplace. Realistic speech sounds like ordinary speech but it has to be invented to convey an area of experience which is not on the surface.

The danger of realism is that whatever sounds like the language of ordinary people will always, in a thoughtless way, be taken to be commonplace. Also, in a snobbish way. In England those accents are thought the ugliest which are identified with the poorest people. Also, in the court of public opinion, which goes on broad impressions, one must not only invent but be seen to invent. But of course artificial heightening needs no more invention than realism. Besides, the realistic writer avoids the prevalent dangers of artificial heightening: routine repetition, rhythm, assonance; and in working within the mould of people’s speech retains checks and balances without which he might so easily drift into consecrated banalities about life, death and love.

Barry Reckord

Act One

SCENE ONE

Outside the school. It’s early and there’s nobody around except CRAGGE, who is waiting for HELEN to pass. He is always glancing up the road till he glimpses her coming and moves away, not wanting to be seen too obviously waiting; but he stays in fu

ll view so she can see him.

Enter HELEN.

CRAGGE: What’s the hurry?

HELEN: Some people have to work. Look at you, bloody boots, holding up the school gate.

CRAGGE: I’m in a match at the school here tonight.

HELEN: Where’s your mates?

CRAGGE: Round somewhere. Colley’ll be here in a minute.

HELEN: Was you waiting for me to pass the school here last night?

CRAGGE: What happened to you then?

HELEN: Was busy.

CRAGGE: Oh?

HELEN: Sylvia says she saw you hanging round.

Helen starts to exit.

CRAGGE: Helen.

HELEN: I gotta get to work. I been late three mornings this week.

CRAGGE: I’m outta school for good three weeks time. (Solemnly.) Pay for you at the flicks then.

HELEN: You’re gonna take me out!

CRAGGE: When I start workin’. I’ll have the money then.

HELEN: Take me out sometime never.

CRAGGE: It’s why I’m leavin’.

HELEN: You won’t get much. I’ve been out three months workin’ hard as hell for me livin’ and not seein’ where the money’s going to. I suppose I see where it’s goin’. I enjoy meself.

Whistle off.

Who’s that?

CRAGGE: It’s Colley comin’ to give me a massage.

HELEN: Where’s Brooksie then?

CRAGGE: Brook ain’t my mate.

HELEN: O ain’t ‘e? What’s massage?

CRAGGE: Loosens up your muscles for a match. You got to be fit and you got to be padded. I have on me thick socks see? Look! And I’ll line them with a pair of exercise books so I’m padded round here… and boots get greased for a big match. Chelsea’s sending over a talent scout.

HELEN: What ‘appened to that rock ‘n roll contest you was in Saturday.

CRAGGE: Come around fifth or sixth but I ain’t really interested any more now. The bastards who put me in sixth said I wasn’t good enough, yet one judge said I was best so where are ya?

HELEN: Didn’t Colley whistle? Why doesn’t he come?

CRAGGE: Don’t know.

HELEN: Is he with someone?

CRAGGE: Who?

HELEN: I don’t know.

CRAGGE: Who did you think?

HELEN: No one.

CRAGGE: Brook.

HELEN: You need football and rock ‘n roll to shine. Other blokes have themselves.

CRAGGE: Who d’ya mean?

HELEN: Well, your mates ain’t always performin’. Brook can just talk ordinary to people.

CRAGGE: ‘Ave you been getting acquainted with Brook?

HELEN: Has anyone been saying I have?

CRAGGE: Well have you?

HELEN: I asked you first.

CRAGGE: ‘E ain’t much good at anything.

HELEN: Sez you!

CRAGGE: What about coming to see the match tonight? Then after we could do something.

HELEN: I might.

CRAGGE: If Brook’s going.

HELEN: Is he going?

CRAGGE: Was it him you was out with last night?

HELEN: What if I was?

CRAGGE: You don’t want to get mixed up with Brook. Saw ‘im the other night with some tart. Disgusting.

HELEN: Doin’ what?

CRAGGE: Was ‘e touching you last night?

HELEN: No.

CRAGGE: On your hon?

HELEN: Yes.

CRAGGE: Say on your honour.

HELEN: On my honour… Disgustin’ doin’ what?

CRAGGE: You don’t want to be at the mercy of the likes of him.

HELEN: Don’t I?

CRAGGE: If it’s him you’re hangin’ around for you should hear what he’ll say about you.

HELEN: Well, I’ll worry when I hear him saying it, not you.

CRAGGE: Did he put his arm round you last night? (He touches her.)

HELEN: Hey.

CRAGGE: I just wanted to see how far you let him.

HELEN: ‘I just wanted to see how far you let him!’ You get my wick. You’re bottom of my list for going out and top a no one’s.

CRAGGE: Brook is top, though.

HELEN: Yes he is. When he talks to a girl his hand ain’t all sweaty to hold from being nervous.

CRAGGE: When he talks to you you’re timid as bloody ‘ell and laugh at any old rubbish he says.

HELEN: No girl would ‘ave you if she could get him.

CRAGGE: Yeah, the world’s full a dunces!

HELEN: No girl will ‘ave nothing to do with you ‘cos you’re square as ‘ell, and next time you touch me I’ll ‘ave your bloody eyes.

Enter COLMAN.

COLMAN: Hello

HELEN: Hello Colley.

CRAGGE: Hello.

COLMAN: (To CRAGGE.) Brooksie’s in the caff. Wants us there.

HELEN: ‘As ‘e got a cuppa ready for us then?

COLMAN: Ask ‘im.

CRAGGE: What about your work then?

HELEN: Oh –

CRAGGE: What’s the time, Colley?

HELEN: Oh, I can stop for a cuppa. (Exit HELEN.)

COLMAN: You comin’?

CRAGGE: You go wiv ‘im.

COLMAN: Come on, it’s Brook.

CRAGGE: Yeah so you go on wiv ‘im.

COLMAN: Your old man ‘it you?... I’ll give you a quick one.

CRAGGE: School’s open.

SCENE TWO

Follows immediately.

Classroom.

COLMAN: Get old Barker’s table, eh?

CRAGGE: O.K. (Exit and re-enter with table.) Good game last night.

COLMAN: Great.

CRAGGE: Last ten minutes couldn’t get hold of the bleeding ball.

COLMAN: Smashing goal that last one.

CRAGGE: You know where I took that shot? Right in the middle of the instep.

COLMAN: I heard blokes say you might play inside left. If it’s fine by tonight there ought to be a bit of a crowd.

CRAGGE: Use Vaseline.

COLMAN: I got linament. The real players use linament.

CRAGGE: What d’you mean, real?

They start the massage.

COLMAN:They’re putting up the nets for tonight.

CRAGGE: Yeah, going to be muddy as hell.

COLMAN: D’you think you’ll be in the team?

CRAGGE: It’ll be a brand new ball.

COLMAN: You can borrow my shin guards if you like.

CRAGGE: Miles Davis the trumpeter says he corrects his own faults.

COLMAN: What’s Miles Davis got to do with football?

CRAGGE: I let mine slide.

Enter BROOK.

BROOK: Massage!

COLMAN: Did you see ‘Elen?

BROOK: Yeah, she come into the caff. I made ‘er late as ‘ell. You comin’?

CRAGGE: Finish me Colley!

BROOK: Stay if you like.

CRAGGE: Colley!

COLMAN: Brooksie’s ‘ere.

BROOK: Are you comin’?

CRAGGE: ‘E’s only just started. (To COLLEY.) ‘E ain’t in the match tonight.

COLMAN: I’ll finish ‘im quick.

BROOK: Then am I gonna stand ‘ere watchin’?

CRAGGE: Just because you ain’t playin’!

BROOK: You mightn’t even be playin’. The team ain’t up yet.

COLMAN: ‘Is name’s in the first thirteen.

BROOK: ‘Is name’s in the first thirteen but only eleven blokes play.

COLMAN: ‘E was best on the field last night.

BROOK: Best on the field my sister’s fanny. All season you’ve been only second eleven. Second eleven all season.

CRAGGE: Because they pick blokes who the bleedin’ headmaster likes and the headmaster likes them that don’t swear…

COLMAN: Don’t smoke and don’t eat in the street.

CRAGGE: What’s swearin’ got to do with football?

BROOK: The old boy can’t play

a bloke who’ll go into decent people’s pavilions droppin’ blue lights can he? ‘E’d lose the manor.

CRAGGE: You’re his mate, ain’t you?

BROOK: ‘E’s all right. If you know they mightn’t put you on the side ‘cos of swearing you’re a big nit to go on swearin’ ain’t you.

CRAGGE: What has swearing got to do with football?

BROOK: But it might keep you off the side yet you go on doing it. You queer your own pitch don’t you?

CRAGGE: Apes, bloody dunces and apes.

Pause.

Old Barker wanted me for this match... swearing an all, but ‘e’s off sick. That’s my luck... Where’s justice?

COLMAN: Old Barker says ‘e’s quite good and needs encouragement.

CRAGGE: Quite good my arse. I come from low down in the school so I’m quite good. If I came from the sixth I’d be a bloody genius...

BROOK: Anyway it’s only a schoolboy match… Ain’t Spurs v. Fulham.

CRAGGE: This bloke’s discovered America.

COLMAN laughs and goes on massaging.

BROOK. (Trying to recoup.) Spurs gonna win, anyway.

COLMAN: We’re backing Fulham.

BROOK: They won’t win.

COLMAN: (Feebly.) They will.

BROOK: They won’t.

COLMAN: (Backing down, to CRAGGE’s fury.) I don’t know, really.

CRAGGE: Fat lot a good just saying they will they won’t. Depends if Fulham is fit, don’t it?

BROOK: It says in the Mirror this mornin’ they ain’t fit, don’t it, Colley?

COLMAN doesn’t commit himself.

CRAGGE: One paper says that, another says different.

BROOK: You’re a brain box, ain’t you?

CRAGGE: The papers say different things. You ignorant nana. One says one thing another says different.

BROOK: It’s luck wins a football match.

CRAGGE: All right then…

BROOK: (Interrupting.) You see ‘em evenly matched yet one wins. It’s a bleedin’ lot a luck every time.

CRAGGE: Listen to what I’m sayin’…

BROOK: Like Fulham winning last week, that was luck.

COLMAN: (To BROOK regretfully.) The papers said it was fitness.

BROOK: (Coming round unconsciously to CRAGGE’s point in a rage.) The papers say different things, one paper says that, another says different.

For the Reckord

For the Reckord